By Richard Freeman

In May 2005 the CFZ undertook our most ambitious expedition to date. A four- man team travelled to the Gobi desert in search of the infamous Mongolian deathworm; a vermiform, desert- dwelling creature said to spit a corrosive yellow venom, and held in much fear by the Mongolian nomads who know it by the name of allghoi-khorkoi (pronounced “olra hoy-hoy”). The team consisted of myself, my two old travelling companions Jon Hare and Dr Chris Clark, and a new addition to the CFZ expeditionary force – Dave Churchill. Dave was a long time member of the CFZ, and wanted to join the Mongolian expedition when it was first mooted several years ago.

Reports suggested that the deathworm emerged after rainfall and lives near sources of water. Therefore, we proposed to try and dam some of the streams in the oasis in order to create localized floods, thus forcing the worms to the surface. Chris also proposed the use of bucket traps. These are buckets buried in the sand. with mesh netting strung between them. The idea is that small creatures would bump into the netting then craw along it until they reached and fell into one of the buckets. We could then examine them in the morning. He also brought some small mammal traps so that we could try to catch potential deathworm prey for examination. We also had some leaflets printed up in Mongolian and distributed throughout the area we were visiting They explained that a group of British scientists would be travelling through the are in May and offered a $50 reward for a allghoi-khorkoi specimen.

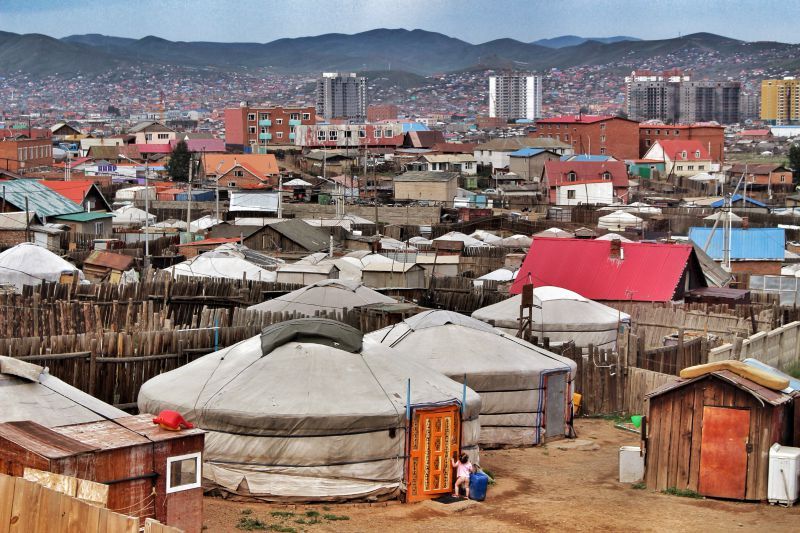

We flew via Moscow (an airport unique in my experience, in not having a bureau-de-change) and on to the capital Ulaan Baatar.

Ulaan Baatar does not look very oriental. It has more in common with Russia and it’s Eastern Block architecture. The Buildings are grey or dull brown and functional. The skyline is dominated by a massive power plant that burns coal and pumps it through big ugly pipe to heat the city. There were a few scattered gurs, the traditional circular, Mongolian tents, in back yards or clustering on the outskirts of the city. It seemed wrong to me that a race of nomads, the people of Genghis Khan, should live in this sedentary manner.

We were met in the airport by Byamba, the director of e-mongol.com , the company with whom we were travelling. Once closed to outsiders during the socialist era, Mongolia is now a popular destination with the more adventurous travellers. Byamba told us that a Canadian company owned the mines and power plant and that the boss was called Richard Freeman!

Dave had set up a website, www.cryptoworld.co.uk in order to chart our adventures. He intended to give regular updates via his laptop, but his USB connection was not working. After checking into the Marco Polo Hotel, we headed to the E-mongol offices to see if it could be fixed.

We were introduced top our guides Bilgee (pronounced Bilgay) a stocky, genial chap, and Tulgar (pronounced Tograr), a slightly shy- looking man in his early 20s. Dave’s connector could not be fixed so he was driven around the city in search of a new one. Whilst he was gone, Byamba tried to contact a man named Boldbaatar who worked as a researcher in the Ministry of Science and Education. Boldbaatar had been researching the deathworm for some time, and Byamba wanted to introduce our team to him.

Boldbaatar claimed that he was just leaving his office on a research trip and would be away for over a month. Byamba suspected that he just didn’t want to share his information.

That afternoon we visited the Natural History Museum. Their collection of dinosaurs is staggering. They included Tarbasaurus baatar the Asian cousin of Tyrannosaurus rex, and Deinocheirus mirificus a huge ornithomimid dinosaur that until recently, was known only from its vast, 8 foot long forearms. It is believed to have used it’s scythe like claws to collect plant material to feed on. Most impressive was a velociraptor and protoceratops locked forever in a dance of death. The predator is clutching the prey’s bony frill, whilst ripping at its stomach with its curved hind claws. The prey is fighting back by biting down on one of it’s foes wrists. Both were buried by a sandstorm millions of years ago and preserved in mid fight.

Afterwards we visited a large market area where iwas jostled several times. I later found out that some bastard had `liberated` my £300 digital camera.

Dave had no luck in getting his USB to work so over breakfast the next day Byamba introduced us to a friend of his called Damdin who was a computer whizz. He worked programming computers for the mining company. He failed to fix the gizmo but took a great interest in our trip. He told us of a man who had claimed to have seen a creature like a yeti only smaller a couple of years ago. However, when the beast was captured it turned out to have been a monkey that had escaped from the circus!

Another story he had was altogether more interesting. His aunt had told him of a dragon that she has seen in a river in the1940s. This happened in the north of Mongolia just after WW2. The animal was dead and protruding from a frozen river. At first, I thought it must have been a frozen mammoth but Damdin said it was long and scaly like a snake. It had been around 100 feet long but only the back was visible above the ice. It had been a very hard winter, so the villagers fed on the dead dragon’s flesh until the spring thaws washed the carcass away. If only they had kept a few scales!

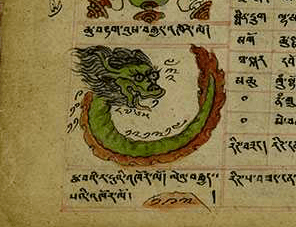

In Mongolia dragons are called luu (pronounced low). It is believed that they live in heaven and only descend to earth on occasion. They bring rain and when storm clouds form around a mountain peak it is called luu hang.

We were introduced to our drivers Togoo and Davaa and the vehicles that would be transporting us for the next month. They were tough little Russian all-terrain vans that had been customized into minibuses.

After breakfast we set off towards the wilderness. On a hill overlooking Ulaan Baatar was a large cairn of stones with a branch protruding. About the branch was tied blue cloth. Bilgee explained that it was an ovoo. Travellers stopped and walked three times round it and placed a new rock upon the pile. This would ensure a safe return. We all added to the ovoo before moving on.

I thought travel in Sumatra took a long time but, it has nothing on Mongolia. The vast distances and total lack of anything approaching roads makes journeys never -ending. We finally reached an area of strange rocks. It looked as if a chocolate ice cream belonging to Godzilla had melted. The brown rocks ran in weird liquid shapes and a sparse wood clustered at their edges.

Bird life was all around. Vast black vultures soared overhead and woodpeckers flitted among the trees. A pair of noisy ravens eyed our camp with interest. Wherever we went in Mongolia ravens were present. It became a piece of expedition folklore that they were the same ravens keeping pace with us like the supernatural ravens of Odin in Norse mythology.

Close to the camp was a very big ovoo with a living tree at its centre. As well as blue cloth there were prayer-flags with the symbol of the air horse (emblem of Mongolia) upon them or representations of the creatures from the Mongolian zodiac that are much the same as the Chinese.

We ate lunch at a tiny conurbation that had the air of a Mexican border town. There happened to be a Mongolian wrestling bout being held in the village, so we went along. Mongolian wrestling seems to be about getting your opponent off balance whilst grappling with locked arms. You are not allowed to kneel or put your hands on the floor. One poor chap was comically outmatched by the Mongolian equivalent of `Big Daddy`

On the third day the terrain became more open and the desert gritty. As we drove Bilgee told me that one of our drivers had been in the area about ten years earlier and had tried to use a well but found it had been covered and locked. Upon enquiring about it, he was told that a dragon had entered the well.

We located the well. It consisted of a car tier, around a hole filled with muddy water. It was only a couple of feet across so the dragon would have to have been very thin to fit into it.

We enquired at a nearby gur. The lady who owned the gur was most hospitable and we were soon gathered around drinking salty Mongolian tea. She told us that ten years ago an old wise man had seen a dragon entering the well. He had ordered it to be locked and said that no water should be taken from it. The local children became afraid.

The story got about, and three government officials came to see him, a this was in the socialist era and the story was deemed to be religious and hence against the socialist thinking of the time. The three men poured oil into the well as a punishment to the superstitious people. Soon after two of the men mysteriously died and the third remains childless to this day.

The woman did not see the dragon herself, but she told us the it was supposed to change colour like a rainbow. To an evil person it would appear black.

That night we camped in the shadows of black, twisted mountains that would not have looked out of place in Mordor. We explored them and I can truly say that the feeling of being watched one gets in eerie places, was stronger here than anywhere else I have ever been

As we drove further south the land became flatter. I truly doff my cap to our drivers and the amazing way they navigate without benefit of roads, or landmarks. The terrain was monotonous. The area we travelled through was known as The Mirror due to its flatness.

Chris and I had Davaa as our driver. Dave and Jon had Togoo. Togoo drove like a madman and had very little trouble. Davaa drove like an old lady and was constantly running into consternation. Twice we were stopped by punctures and once we suffered an overheated engine. En route we saw a swarm of black vultures around the carcass of a horse. We also glimpsed some rare black tailed gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa) in the distance.

We stopped to dine at an area known as Long Red Mountain. One again the chameleon-like Mongolian countryside had changed. Now it resembled the ruddy surface of Mars. Long Red Mountain is famous for its dinosaur fossils and fossil eggs. It is one of the places palaeontologist Roy Chapman Andrews visited in the 1920s. He was looking for fossil humans but discovered dozens of dinosaur nest sites. The discoveries continue to this day. Some German tourists had found an ancient egg just last year.

We thought we would try our look and split off to search for fossils. I was looking along the sides of embankments where small landslides had occurred when my eyes fell on a perfect fossil egg. It was a little larger than a hen’s egg and more lozenge shaped. There were tiny cracks running across its dusty grey surface. Excitedly I reached down to grab it with thoughts of presenting it to the natural history museum in Ulaan Baatar. It instantly crumbled to dust in my palm. It was nothing but desiccated camel shit!

I was laughing at this when the sandstorm blew up. It came from nowhere, a screaming red storm that lashed the sand into a frenzy and tore at the skin and eyes. I stumbled back to camp and we drove away. It was like driving through aggressive fog.

We finally drew clear of the storm and passed a well. Around it were gathered nomads with herds of sheep, goats, camels, and horses. Water was been drawn up via a bucket on a rope attached to a wooden, hinged, weighted tilt. The weight counterbalances the water bucket making drawing it up far more easy. It is a tradition in Mongolia that when travellers pass a well in use they stop and help draw water for the livestock, so we all took turns filling the troughs for the animals.

One of the nomads offered me a ride on a camel, a grumpy looking beast that was kneeling in the dust. I accepted and began to mount it when I committed a dreadful faux-pas in camel etiquette. When mounting the ship of the desert one is meant to throw one’s leg between the beast’s humps then insert your other foot into the stirrup closest to you. I put my foot in the stirrup before throwing my leg over. The indignant camel screamed in fury and turned its head round to face me with a look of pure hatred. Bearing nasty yellow tusks, it reared up and threw me to the floor and attempted to run off into the wilderness. It took three men to regain control of the beast. It must have got the hump.

We decided not to camp that night and stayed with Davaa’s family in Mongolia’s second city Dalanzagad. The Mongolian equivalent of Birmingham made Ulaan Baatar seem like Venice or Prague, but it did have an internet café were Dave could update the website.

Jon and Dave were accosted by a drunk who told them that they were fools to hunt for the allghoi-khorkoi as it had “killed thousands of people”.

On the outskirts of Dalanzagad lived one of the witnesses who had seen our posters and contacted Byamba. Luvsandorj was a 90- year -old former policeman. He lived in the Gur district of the city. He invited us in and following the tradition offered us some snuff from a bottle. I had never had snuff before, and thinking it churlish to refuse, I took a hearty pinch and shorted it up one nostril. I almost fell over with a fit of sneezing – much to the amusement of our host.

It had been 1930 when Luvsandorj had seen the death worm. He was 15 back then and had been tending to cows when he came across a two foot long, reddish brown creature in the desert. It was about 4 inches thick and he could see no eyes or mouth on it. It was sausage shaped and moved slightly from side to side. He ran to tell his parents who warned him not to go near it ass it was deadly. He drew a picture of what he had seen, a crude sausage shape. He provided us with the names and addresses of other people he knew that had seen the creature.

As we drove into the desert, we saw what looked like a huge, shimmering lake overlooked by mountains. As we got closer, we saw it was a titanic mirage. We camped in the freezing desert beneath weird black rock vistas.

Next day we travelled deeper into the wilderness and tracked down one of the people on Luvsandorj’s list. Juuraidor was a 70 -year- old camel herd who saw the worm in the 1950s whilst searching for lost camels. His description tallied with that of Luvsandorj’s. Brown, two feet long, and with snake-like scales. He had heard that the worm was dangerous, so he ran away. The encounter was in June. He also told us of a man who had put a death worm on an iron plate. The plate had turned green. Another man that he knew, had wrapped a dead death worm in three layers of felt. The worm shrivelled up like a piece of leather, and the felt turned green. Both incidents had been long ago, and no remains had been saved. Later that day we saw a group of rare Mongolian wild-ass (Equus hemionus hemionus), galloping across the dusty horizon.

We had now entered the Gobi proper. We made camp in a rocky valley. Two men drove into the camp the following morning and introduced themselves. One was a grizzled park ranger the other a younger man with prominent golden teeth named Nyama. The latter had seen the death worm on no less than three occasions.

The first was in 1965 when he saw the creature’s head (presumably) protruding from a hole in the sand. The following year he saw a specimen in the process of swallowing a mouse. Finally, he actually killed a worm – in 1972 – by throwing a rock at it. Some Russian scientists who had been in the area studying snakes took the body away. It probably resides forgotten to this day in some Russian museum basement.

Nyama said the worm eating the mouse was grey and 10 inches long. The other two were brown. The one he killed was between18 inches and two feet long. They moved with a caterpillar like motion. The sightings occurred in a place called Dun-dus. He also heard tell of a death worm killing a child by spitting venom but could not confirm this.

The park ranger and his family lived in a nearby gur. His wife had seen the worm just three years ago in an area close to the Chinese border. He invited us into his gur whilst we waited for his wife. He had an impressively large collection of goats and some huge, savage- looking guard dogs. Despite an intimidating display of barking, the dogs were actually quite friendly. I found this to be the case right across Mongolia.

He offered us a drink of fermented camel’s milk whilst we waited. It tasted like fizzy, alcoholic yoghurt. It made a nice change from salty tea and I drank two bowls of it, an action that I would later come to regret.

When Sukhee, his wife, turned up she agreed to take us to the spot where she had seen the creature and remained with us for several day’s hunting.

As we were close to the Chinese boarder we were stopped several times by amiable but Kalashnikov toting guards who checked our passports. One had heard about our expedition on the wireless. Byamba pointed to a nearby range of hills and told us “That marks the border with China” The hills were just 20 miles away.

The ground was now sandy and full of rodent burrows. A low forrest of saxaul grew. As we wandered through the stunted woods Sukhee saw something and began to dig. She pulled a light yellow, ugly root from the ground. It was waxy in appearance and was covered with soft spikes. It was the root of the goyo plant and much admired by nomads. We shared the root which tasted surprisingly good, rather like a cross between banana and celery. Were they idea goyo is poisonous originated I have no idea. It made very good eating.

She led us the spot where she had seen the strange beast. She had been herding cows with her son when she saw an 18- inch, grey, worm-like thing slither out from a hole. Her son threw a rock at it and it slid into some bushes. She ran away. It had been in September and it was very hot, about 40 degrees Celsius.

Sukhee told us there were two worms in the desert. One was the allghoi-khorkoi or intestine worm. The other was called the temrenii suhl or camel’s tail. This was smaller than the deathworm and grey rather than red – brown.

After a search of the area we decided to make camp. Just after lunch a particularly savage sandstorm blew up. It tore down our tents and blew over our tables. We retreated to the safety of the mini-buses but my stomach was bubbling loudly on account of the fermented camel’s milk. I had to brave the stinging sands and make a run for a bush. Having explosive diarrhoea in the middle of a sandstorm is not something I would like to repeat!

Sukhee told us that the storm would last for the whole night. It was imposable to camp, so she invited us back to her gur. The family had two gurs and allowed us to sleep in one of them.

Dave’s laptop caused much interest as he had moving film with sound on it. The whole extended family crowded into the gur to see it. It was like a small, crowded, circular cinema. Many of the Mongolians (including Bilgee) had never seen the sea and were fascinated by Dave’s film.

We travelled back the Dalanzagad and as Davaa’s family were away we checked into an ugly hotel and spent the night at Dalanzagad’s answer to Stringfellows.

Next day we drove deep into the Gobi heading for the frozen gorge, a river that never thaws. We visited the Gobi Museum, surely the remotest museum on Earth (unless there’s one in Antarctica ). Among the wide array of stuffed animals was a carving of the death worm. Adam Davies had seen and photographed this a couple of years earlier. It resembled the witness descriptions apart from having clearly visible eyes.

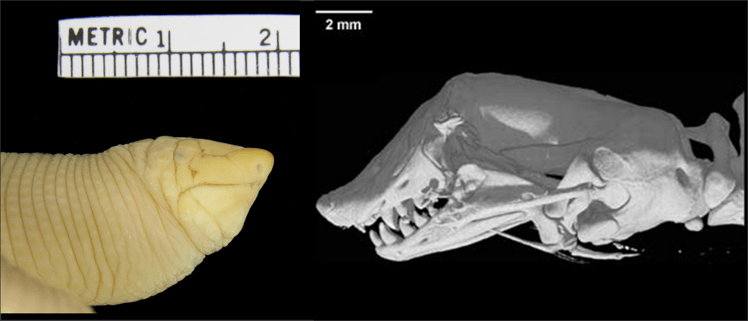

The creature was labelled as a tartar sand boa. Via Bilgee, I enquired as to why this was. The museum guide said that the carving had once been labelled as a allghoi-khorkoi but the label got tatty. He was at a loss to know why it had been relabelled a sand boa.

The tartar sand boa (Eryx tatricus ) does bare a slight resemblance to the death worm descriptions. It is a brownish or greyish, chunky snake that can reach four feet in length. The end of its tail is noticeably thick. However, it has a clearly defined head and visible eyes. It ranges from the Caspian Sea to Western China. It probably occurs in Mongolia as well. The sand boa is a constrictor and does not produce venom let alone spit it.

We camped in a valley full of pikas (Ochotona pusilla) , small lagamorphs related to rabbits and hares. The next day we set off for the gorge. Yolyn Am is a frozen river. Protected from the sun’s rays on each side by sheer 500 -foot- tall cliffs. At one time the river never thawed even in the height of summer. But from 1980 onwards it has begun to thaw in summer. Perhaps this s a further indicator of global warming.

When we were at Yolyn Am the river was frozen. The ice was thick enough for us to drive the mini-buses along it until a sheet gave way with a sickening crash and engulfed the back wheel of the one I was riding in. We had to tow it out.

Continuing on foot we found an ovoo built on the ice and some amazing ice caves. Where the lower layers of ice had melted, they left blue and silver caverns in the frozen river. We crawled inside for a closer look. Weird fissures and troughs had been carved out of the ice by the wind.

In a small cave by the riverside, Chris left a geo-cache, a plastic container with the details of our location via satellite and details of the CFZ website so that whoever found it could get in touch.

Bilgee said that this area, an eastern outcropping of the Alti Mountains, was one of the best places in the world to see snow leopards. On three of his four trips there he had seen one and Togoo has also seen one killing a wild sheep. Sadly, we were not so lucky.

We met a group of men selling stone carvings. One of them, an incredibly talented man called Baiar carved me a dragon in one hour flat.

That evening a massive sandstorm blew up turning the sky a reddish grey. Deciding not to camp we stopped in a small town and slept in a minute hotel with unreliable electricity and a constantly banging door.

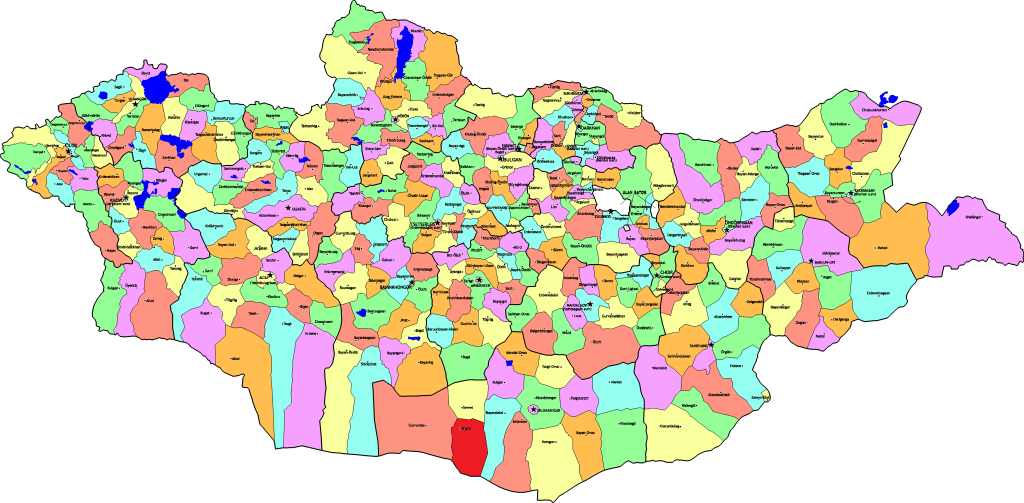

Striking on in the morning we reached Noyon Sum. A sum is the Mongolian equivalent to a British county. Some sums are the size of Scotland. In the Sum Centre, (the largest and most important town in the sum) we had a meeting with the governor of Noyon. He had never heard of the death worm but received the leaflets Bilgee had distributed. The governor did some digging and found out that in 1955, a man herding sheep had come across a two- foot- long, grey creature with no discernible head or tail. The man fled in terror. He now lived in Dalanzagad.

The governor had found more stories. His driver told us that in the 1960s his mother in law had seen a death worm. It was light grey and making holes in the sand. She ran away from it. The governor had found another local man named Damdin who had seen the creature in 1954-55. He gave us his address and we thanked him heartily and went on our way.

After a roundabout drive we found the gur belonging to Damdin’s sister. She told us that her mother had seen it as well, also in 1955. She had been present at the sighting but was too young to recall it. Her mother said it was 2- feet- long, brown, scaly, and as thick as a gur support pole (about 5 inches). She gave us directions to her brother’s gur.

We found Damdin’s domicile and he welcomed us in. He told us he had been out tending camels in May 1955. At about ten in the morning he saw a death worm. It was brown, two- feet long and about two inches thick. It made no movement. He ran to tell his parents and they warned him it was venomous. He returned to the spot he had seen the creature in, and it was gone.

Damdin’s family had been so frightened by what their son had seen that they packed up their gur and moved. He said that lots of families moved after seeing a death worm. He heard tell of it killing animals by spitting at them.

He took us to the area where he had seen the worm. The marks of his family’s old gur were still visible in the gravel. The area was much disturbed by camel tracks. We felt it unlikely that the worm still inhabited this part of the desert. Another storm forced us to spend the night in the gur of one of Damdin’s friends.

We moved on again to stay in another gur deeper in the Gobi. The one we were supposed to be staying in was flooded but a second was available. There was rancid surface water all over the area and sulphurous smelling salt caked grasses.

The valley was overlooked by an old telecommunications tower from the socialist era. We explored some crumbling barracks dating from the same period. Behind these was an old Buddhist temple with ornately carved pillars, some of the original colours still visible. The temple had been destroyed in the anti-religious purge of the 1930s. What was left had been incorporated into the barracks. Deep in the bowels of the temple, beneath some old floor boards I found an offering, mouldering money wrapped in a blue cloth. It seemed that even in the height of socialism the faith had not been totally extinguished. I added a little of my own money and reburied the offering.

Further beyond the temple was a weird landscape, an oasis of mossy, green, humped tussocks that looked more Irish than Mongolian.

The next day Bilgee took our passports to be checked at a military base. We were once again drawing close to the Chinese boarder. He returned with a retired Mongolian Army Colonel called Hurvoo who wore a broad ten- gallon hat. He had once been in charge of a base called Ovootin Otriyad.

In 1973 he had been patrolling an area called Ulann Ovoo on motorbike. It had been in May and at sunrise. He saw what looked like an old tyre in the desert. It was some sort of animal lying coiled up. His description was by now familiar, brown, two feet long, scaly and sausage- shaped. He did say he saw light playing across it like electricity or light reflected from a mirror. This may well have been the rising sun reflecting off its scales. It had been raining and the worm was wet.

Hurvoo watched it for half an hour and it did not move. He drove off to get a camera but on his return it had gone. One year later a solider reported that he had seen an identical animal. Hurvoo investigated but found nothing. He believed the worm came out after rainfall.

We drove out to the area after checking in at the military camp again. We set bucket traps in the scrub. These consisted of a series of sunken buckets connected by netting supported by struts. The idea is that a creature bumps into the netting and cannot continue forwards. Ergo it runs along the netting until it comes to a bucket and falls in. Then you have a specimen. We also set baited small mammal traps to see what possible death worm prey might be in the area.

That night we stopped at the military base. A thunder storm occurred during the night with heavy rain. The next day we rose early to check the traps. Both the bucket traps and the small mammal traps were empty.

We moved on to Gurantes Sum and stopped in hotel shaped like a huge concrete gur. We had a meeting with the governor of Gurantes, Deevat Serem who had distributed our leaflets in the area. He had a witness named Khuuhengaa with him. She had seen the worm in the 1980s when she had been a girl. She could not recall the exact year, but it had been in summer. She was staying with her grandfather who called her to see it. The worm was 15 inches long, brown and with no discernible head or tail. Her grandfather told her it was venomous and she was afraid.

Deevat told us of another sighting that occurred just last year. A man had been cutting reeds at an oasis called Zulganai. A man cutting grass lifted up the worm on the end of a stick and threw it away. Another man had seen the worm at the same oasis and claimed he could identify it’s tracks and burrows. Deevat was sure the worm exists and told us that in these days it is seen less often. This is not because it is getting less common, but people are now travelling by motorbike rather than by horse or camel. Also, people are moving to towns, cities, and areas of sedentary residence rather than moving about as they used to. Hence the deathworm is encountered less often. We identified three oases that we thought might be promising places to look given that the death worm was found close to water. He thought that the dragons seen in wells were just metaphors for poisoned water or ways of keeping people from drinking bad water.

The morning found us back on the trail again. We tried to locate the man who could identifiy death worm tracks but he was not at home. We found the gur of Batdelger, the man who had seen the worm in 2004 at Zulganai. His wife and son also saw the creature. They had been cutting grass to feed livestock at the time. His description differed slightly from the others. The worm he saw was 15 inches long and brown. It had a squarish head and what looked like large eyes, but these may have been part of a pattern on the skin.

He did not think it was a snake as it was too thick. His son lifted the worm on a branch and cast it away. It felt very heavy.

We spent the night in a gur belonging to the family of the former local govenor. The next day we spoke with his wife who had seen an allghoi-khorkoi in 1957 in an area close to the Chinese border close to were Colonel Hurvoo had seen it. Once again our suspect was 15 inches long, brown and had no clear head or tail.

The ex-governor himself spoke to us and said he knew a man who had seen three large snakes some years ago. The biggest was six feet long and had a head shaped like that of a sheep. All three sported horns.

There are horned snakes known to science. They include the rhinoceros viper (Bitis nasicornis) and the horned viper (Cerastes cerastes). Their horns are in fact modified scales. However, none is known from Mongolia and none reach six feet in length. We were unable to locate the witness.

A long boring drive followed. At last we came to an area of spectacular cliffs and mesas. The looked like gigantic petrified flames. Between these spectacular edifices was Wall Canyon or Zuun-Mad, the first of several oasis we intended to visit.

Water had cut low but sheer cliffs in the sandstone. A stream ran through them surrounded by poplar trees, saxaul, tamarisk and other plants. We split up to explore and I followed the path the water had cut into a narrow steep side valley. A short- eared owl (Asio flammeus ) exploded out of a bush about five feet away causing me to jump out of my skin.

Later we set up the bucket and small mammal traps again. The physical nature of the oasis with its steep sides made the damming plan impractical. In the twilight the colour of the rocks changed hue as you looked on. It was a spectacular display that looked more like special effects than a natural occurrence.

We decided to explore Wall Canyon after dark and set off with torches. Dave’s beam picked out a pair of large, luminous, green eyes. We tried to get a closer look, but their owner had vanished.

At day break we examined the traps. Apart from hordes of ants they were empty. We all saw the owl again. Short-eared owls, unlike most of their kin will often hunt in broad daylight. The riddle of the green eyes was solved that night. They belonged to a Przewalski’s skink gecko (Teratoscincus scincus ) .We saw dozens of these attractive little lizards, their outsized eyes glowing green in the night. We caught several. Their luminous eyes give the illusion of a much larger creature.

Next day we moved on. Another epic drive brought us to the largest collection of vegetation we saw in the whole Gobi, the oasis of Zulganai. This was a mile- long march with steep cliffs at one side and a kinder slope at the opposite side. It was filled with reed beds as tall as a man. At one end a narrow strip of woodland erupted and the oasis formed a second smaller pool. The water course ran on to be lost in the desert. Large, savagely horned bulls pranced through the reeds adding a little extra spice to the exploration.

We descended into the reed beds. There was much bird life including demoiselle cranes (Grus virgo) , spoonbills(Platalea leucorodia), and white storks (Ciconia ciconia) . We say the strange flowers of the goyo erupting from the earth. These consist of reddish, phallic like buds that bring forth masses of tiny violet and blue flowers. They look a little like lupins.

We made camp and as dinner was being prepared, we watched a whirlwind forming in the distance. It had started as nothing more than a dust devil but rapidly grew in size. We watched it with interest filming it as it slowly drew closer and built in size and power.

It approached the valley that curled up over the lip of the cliff and was upon us in seconds flat. Screaming like an angry djinn it tore through the camp shredding the tents and hurling dinner to the four winds. I was slammed against one of the min-buses and found myself in the eye of the twister. Togoo was entangled in the remains of a tent and dragged along the desert.

Then just as swiftly as it had come upon us, it was gone, sweeping out over the dusty plains and into the horizon.

The camp had been totally destroyed and night was falling. We had no choice but to drive 75km back to Gurantes and spend the night in the stone gur. It was as if the desert was rallying its powers against us jealous of its secrets.

We drove out to the third oasis, Hermen Tsav the next morning. This was a small wood of poplar trees. It was much drier than theyothers and far more used by humans. An animal corral had been erected at the centre of it. There was little wildlife. Thankfully we had back up tents. Jon and I started one with pictures of grinning clowns. Adam Davis had told us of this very tent the year before.

That night Tulgar soundly thrashed Jon and I at Mongolian wrestling and Bilgee told us a strange story about a haunted gur. Back in the 1970s a sombre socialist newspaper reported that a Russian geologist had been attacked by a ghost in an empty gur. Gurs that are not in use are often stocked up with fuel, food, and water for fellow travellers to take advantage of. In a land as inhospitable as Mongolia this is a necessity rather than a kindness.

The geologist and a colleague were staying in such a place one night. They had been playing cards. The geologist looked up to see the inside latch on the door turn and open by itself. His friend did not seem to notice it. Presently a woman in a red deel (a long heavy Mongolian coat) entered and tried to strangle him. His companion was oblivious. He finally managed to kick over the card table where upon the ghost vanished and his friend looked up.

In the morning we drove back to the second oasis from which the whirlwind had driven us. Exploring the second smaller pool we discovered the tracks of several wolves going to and from the water source. We followed the tracks and the stream that fed the oasis into the desert. We tried to find its source but it became lost among the trackless sands and we were pressed for time.

We found another smaller pool that had methane bubbling up from it and releasing foul smells. That afternoon Bilgee discovered that one of the vans had a badly damaged axel and it had to be driven to the nearest (Sevree Sum) town for repairs.

Next day we took the long dull drive to Sevree Sum. We saw a tornado on the way that dwarfed the one that destroyed our camp. We filmed it from a distance this time.

When we arrived in town, we checked into a tiny hotel. The matronly owner cooked us some delicious meat dumplings. The governor had heard of our arrival and invited us into his gur. His name was Tserendorj and is hospitality overwhelmed us. He told us that he was delighted that we were visiting him and that he did not think that scientists from abroad would be at all interested in meeting him. He seemed to think we were far more important than we actually were.

Tserendorj was a mine of information and together with his friends and family we consumed much vodka during a fascinating evening. He related a story of an old man who had seen the worm in 1957 in an area of the Gobi now owned by China. It looked like a length of blood- filled intestine. The same old man heard of a fellow prodded it with a horse goad and the end of the goad turned green. Both horse and rider died. This is reminiscent of stories of the basilisk in medieval Europe. Another man had seen it during the 1950s. It slithered out from under a rock and the witness threw a stone at it. The worm retreated back under the rock.

The governor introduced us to a 93- year- old man whose grandfather had seen the worm in the 19th century at the oasis we had just left. He thought use of motorized vehicles and the population moving to towns was the reason that the death worm was now seen less often.

He did not buy the idea that well dwelling dragons were metaphors for bad water at all. He insisted that they were real creatures (and I am inclined to agree with him). He told us of a doctor from Ulaan Baatar who had seen such a creature in a well just last year. This had occurred in Bulgan Sum. The doctor described what looked like a green- scaled Chinese dragon coiled at the bottom of a well. Understandably he was shocked. This was no nomad or peasant but an educated man.

The governor had also spoken to a man who had seen a horned snake in his youth. It was over two 6-feet-five inches long and sported two horns. He found it outside of his gur as a child. It did not seem aggressive and he played with it.

Years later the man’s wife died after a five- year illness. A shaman told him that it was because he had touched God’s sacred creature as a boy.

The governor invited us back next year to join in the celebrations for the 80th anniversary of his Sum.

On the morrow we were back on the road. We stopped at Bulgan Sum but were, frustratingly, unable to locate the doctor. A beautiful teenage girl was selling unusual stones she had found in the desert. I brought a couple of pieces of petrified wood from her.

That evening we visited the famous flaming cliffs where Professor Roy Chapman Andrews had discovered the first dinosaur nests and eggs in the 1920s. We stopped at a nearby holiday camp consisting of rows of gurs.

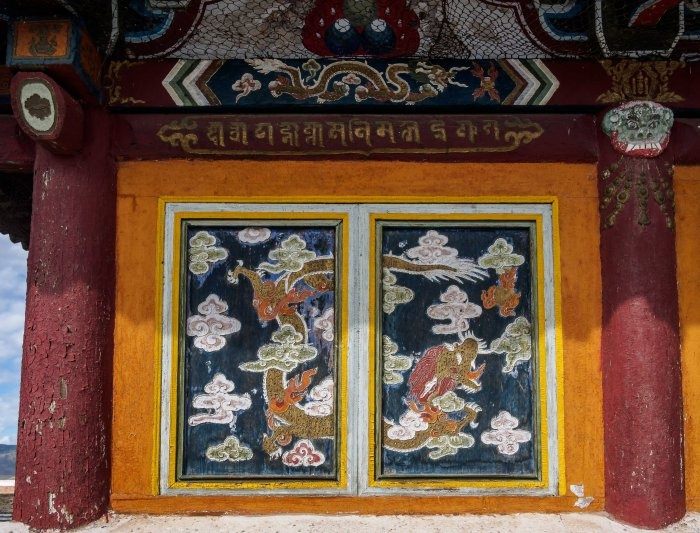

The expedition was all over bar for the shouting now. The next couple of days was nothing but a dull journey back towards the capital. We had a brief look at a Buddhist monastery that had escaped the anti religious purge of the socialist days by becoming a warehouse. Once Mongolia had thrown off the yolk of communism the temple reopened. There were interesting carvings of daemons. Before the coming of Buddhism, the Mongols were animist. When Buddhism arrived, it absorbed the old animist gods. It turned them into daemons but ones that had converted to Buddhism and were ferocious, zealous guardians of the faith.

We contacted Byamba and asked him if he could try to contact the doctor who had seen the dragon or find out his address in Ulaan Baatar.

We had one day staying in the “melted chocolate” valley. Dave almost got himself killed climbing up a mountain.

Finally, we made it back to Ulaan Baatar and checked into the Marco Polo Hotel again. The next couple of days were spent around shops, museums and temples. We visited the library to see if we could turn up any information on the death worm. They had nothing on the worm but did have a massive block of stone intricately carved into entwined dragons. It formally sat upon another block onto which had been carved untranslated script. It had been found in the desert some years before.

We were unlucky in so much as that nature was against us. May 2005 was colder and more windy that the norm. We intend to return one day in more clement weather.

Byamba is still trying to track down the doctor who saw the dragon. So far, he has had no luck.

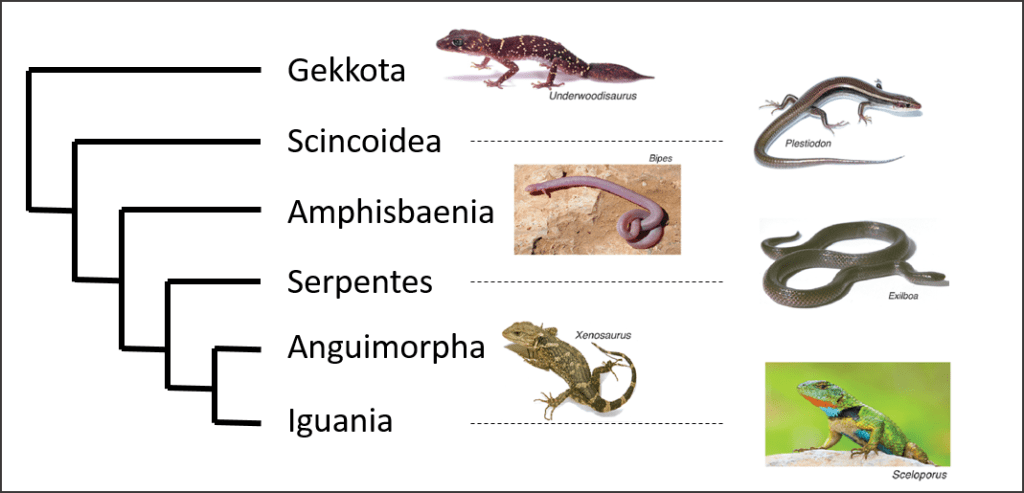

I believe that the death worm is one of two things. It could be a worm lizard or amphisbaena, a group of primitive burrowing reptiles that are not worms, snakes or lizards, but are related to the latter two. Poorly studied, little is known about these creatures, but they resemble the descriptions of the deathworm. Indeed, they take their name from a legendary snake, the amphisbaena that had a head at each end of its body.

Another possibility is that it is an undiscovered species of sand boa, a sausage shaped constricting snakes often found in arid climates.

Neither worm lizards or sand boas are venomous, but strange beliefs can grow up around harmless creatures. In the Sudan the natives believe that the sand boa is so deadly that one only has to touch it and the venom will soak through your skin and kill you. They call the sand boa the apris and go in great fear of it despite that fact that in reality it is harmless.

There could well be a species of horned snake in Mongolia probably a form of large viper. As for the dragons, well the massive international accumulation of sightings and folklore convinced me of their existence a long time ago.

I have e-mailed Byamba some pictures of worm lizards and sand boas to show to witnesses he speaks with. Perhaps they will see something they recognise. For the time being the wind haunted, desolate Gobi is keeping its secrets.

Richard Freeman eminent member of the Center for Fortean Zoology, he is the very definition of the cryptozoologist: an enthusiast, an adventurer, a writer, a free-thinker, someone who devotes his life investigating the mysteries of the animal world, all over the world. His latest book is available here.

Un commentaire